Our group employs stable isotopes to advance our understanding of the ocean’s biogeochemical cycles, both in the modern and across Earth’s history. Our laboratory is uniquely equipped to measure trace amounts of nitrogen in low-nitrogen samples, such as organic nitrogen preserved in fossils and nitrate in seawater. This specialized capability enables us to address important questions in Earth and environmental sciences.

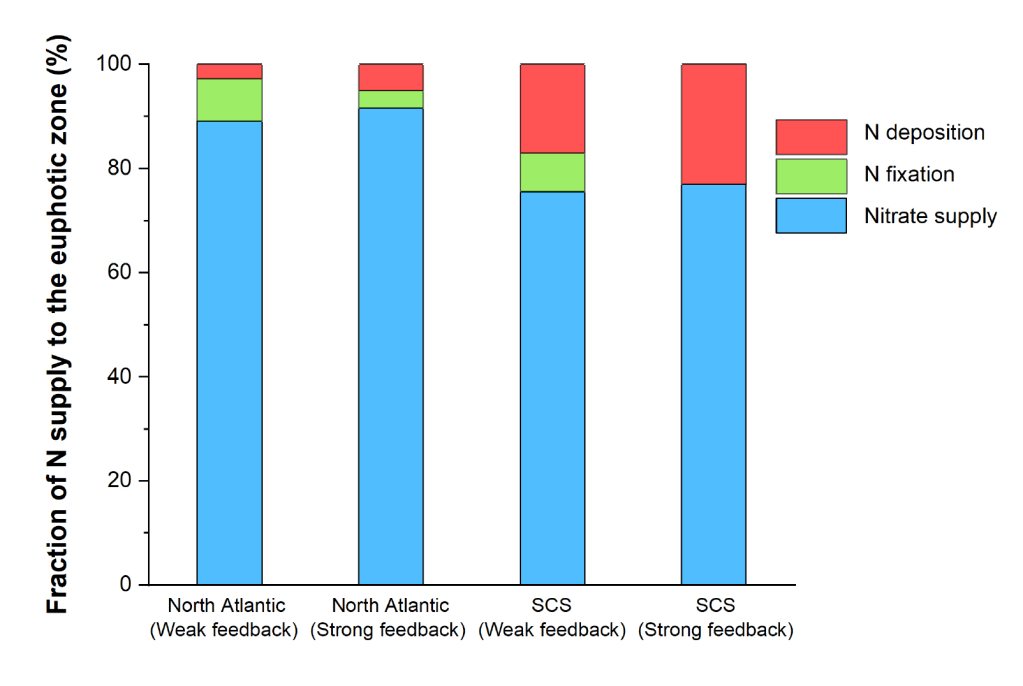

Anthropogenic nitrogen in the ocean

Human activities have been altering the global nitrogen cycle through fertilizer usage and fossil fuel burning. Currently, humans generate fixed nitrogen (i.e., biologically available nitrogen) at a rate exceeding 200 million tons per year, which is comparable to the rate of natural N2 fixation on the entire planet (200-250 million tons per year). Over half of this anthropogenic nitrogen finds its way into the environment, resulting in significant consequences such as eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, water hypoxia, and increased greenhouse gas production (e.g., N2O and CH4). However, the impact of anthropogenic nitrogen on the ocean is complex and not well-understood, primarily due to limited oceanic and atmospheric measurements. In our study, we use nitrogen isotope analyses of seawater and biological archives (e.g., corals) to trace the distribution and fate of anthropogenic nitrogen in the global ocean.

Ocean deoxygenation: Past, Present, and Future

Oxygen is fundamental to sustaining marine ecosystems. However, the ocean’s dissolved oxygen has been declining over the past several decades, a trend known as “ocean deoxygenation”. Predicting future changes in this process is crucial for protecting marine ecosystems and supporting human communities that depend on fisheries. In our lab, we employ stable isotope analyses to investigate both current and historical variations in ocean deoxygenation across various timescales. Our research encompasses oxygen-deficient zones in the open ocean as well as coastal hypoxic regions.

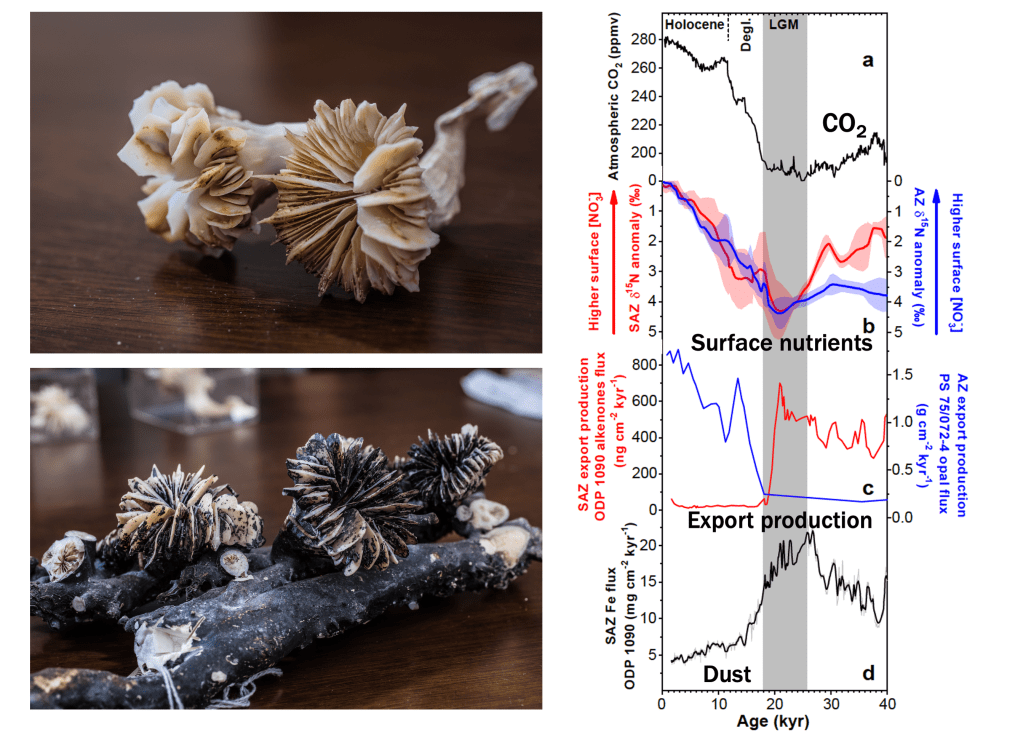

The ocean’s biological pump and atmospheric CO2

Atmospheric CO2 levels have fluctuated throughout Earth’s history—even before significant human influence. Gaining a deeper understanding of natural CO2 variations, such as those associated with ice age cycles, has important implications for the future fate of anthropogenic CO2 and can facilitate the development of nature-based solutions. A key factor influencing atmospheric CO2 variability is the ocean’s biological pump, particularly in regions known as “high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll” areas. In these areas, phytoplankton productivity is limited not by major nutrients (i.e., nitrogen and phosphorus) but by the micronutrient iron. Changes in the supply of iron may have affected the efficiency of the biological pump, thereby altering CO2 storage in the deep ocean. In our lab, we use stable isotope analyses to investigate the influence of the biological pump on atmospheric CO2. This research contributes to the development of marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) technologies, such as iron fertilization.

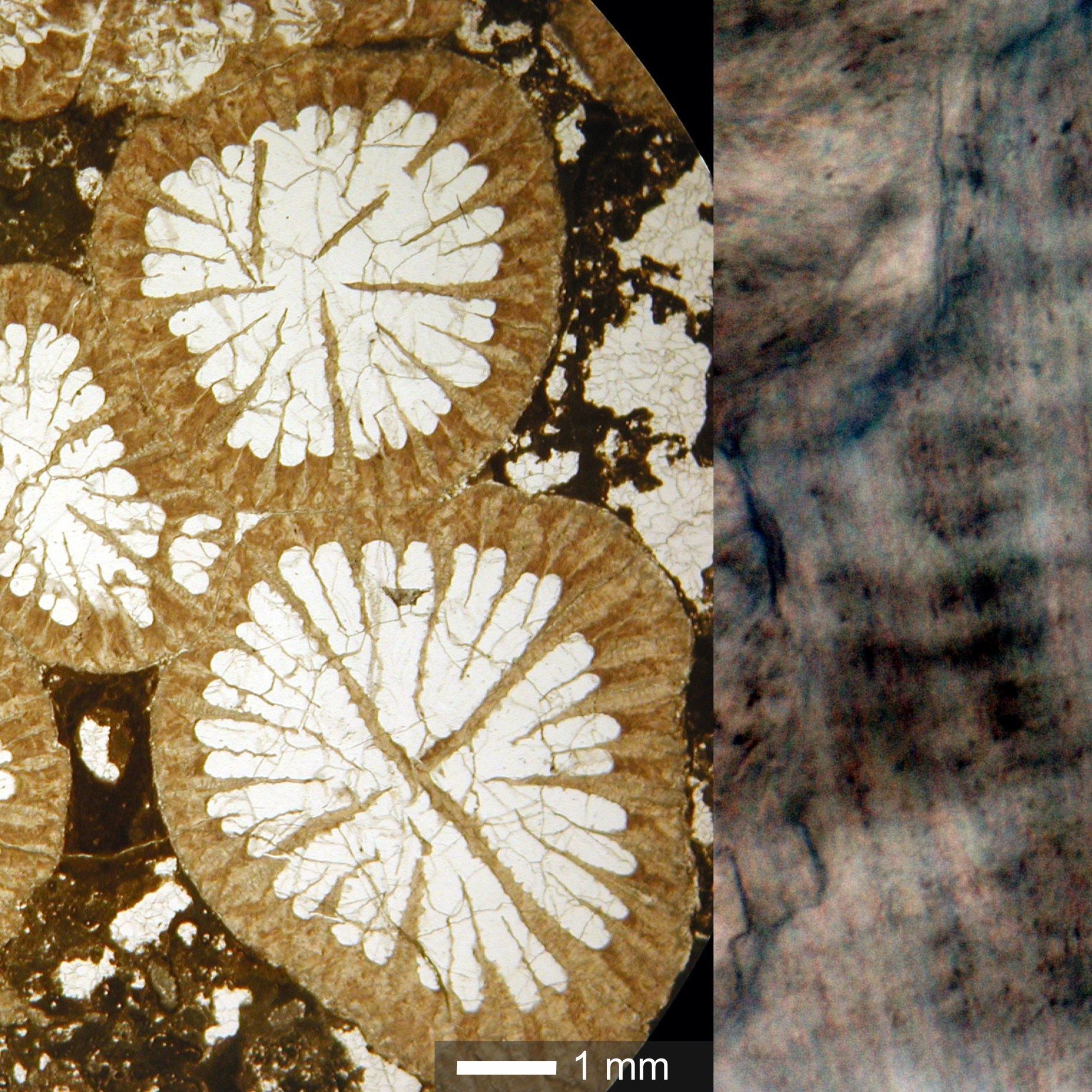

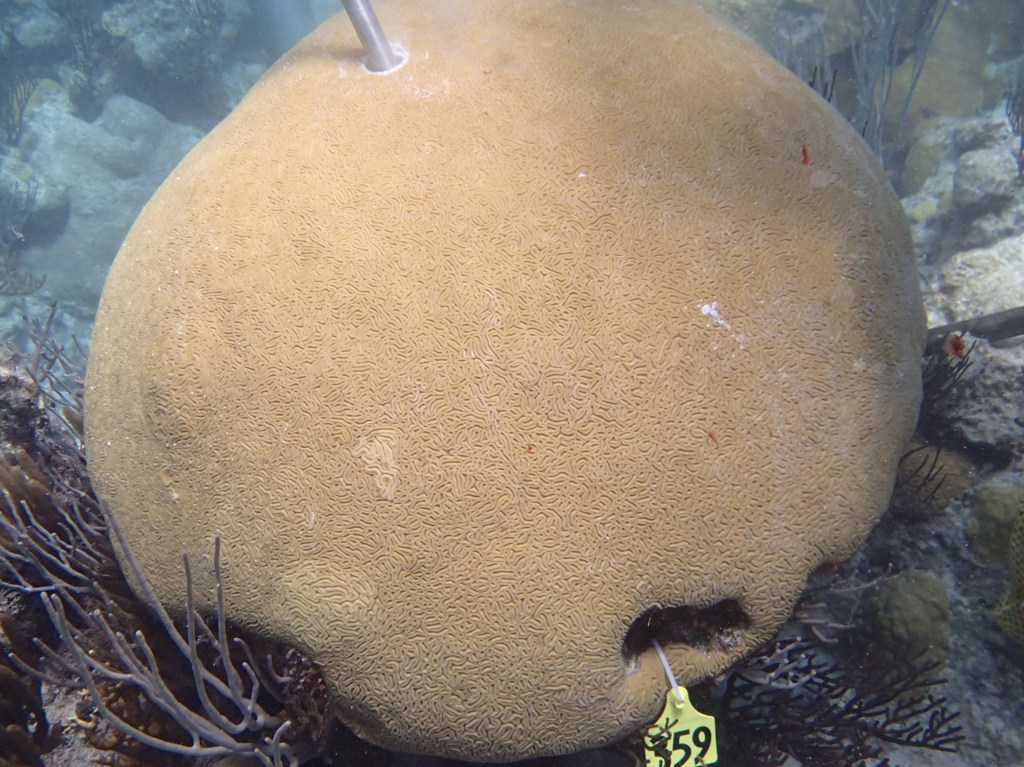

Anthropogenic impacts on coral reefs

Coral reefs, home to at least a quarter of all marine species, are increasingly threatened by human-driven stressors. Reef-building corals live in a mutually beneficial partnership with photosynthetic algae that are housed within their tissues. When environmental conditions deteriorate, such as with rising temperatures and nutrient pollution, corals can lose these algal partners in a process known as coral bleaching. This breakdown of symbiosis reduces coral growth, increases mortality, and can ultimately drive reef degradation and disrupt food webs. Understanding how coral symbiosis and reef food webs responded in the past, especially during warmer intervals, can help constrain the future trajectory of coral reefs. We use nitrogen isotopes to reconstruct the history of coral symbiosis and trace shifts in reef food web structure through time.